Is there a civet in your perfume?

Is there a civet in your perfume?

3 06 2007One of the most curious aspects of dating and relationships in technologically advanced countries is the need for people to cover up their natural scent with lots of different products. For my own part, my current shampoo, conditioner, body soap, deodorant, and cologne are all different, and I douse myself with foreign scents to make sure that I do not offend the olfactory sensibilities of others. But where do such scents come from? There are plenty of synthetic chemicals that mimic naturally (or unnaturally) occurring scents, but, interestingly enough, some fragrances still require animal sources. As Terry Pratchett wrote in The Unadulterated Cat (which ironically sits next to a basket of the products I mentioned above in the bathroom);

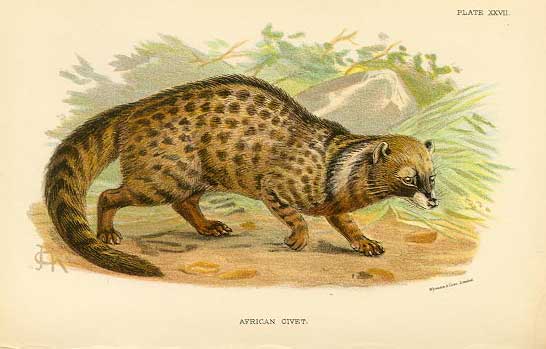

An 1894 Richard Lydekker painting of an African Civet

The civet cat has been a nervous animal ever since it discovered that you can, er, derive civetone* from it and use it in scent. Exactly how this is done I don’t know and do not wish to research. It’s probably dreadful. Oh, all right, I’ll have a look.

It is.+

*A 17-member ring-ketone, according to my dictionary, as opposed to the mere 15-membered muscone from the musk deer. Does the civet feel any better for knowing this? Probably not.

+Who invents these scents, anyway? There’s a guy walking along the beach, hey, here’s some whale vomit, I bet we can make scent out of this. Exactly how likely do you think this is?

Indeed, the civet’s (specifically the African Civet, Civetticus civetta) scent is also useful to those wishing to track big cats, a researcher in a recent issue of Natural History relating that central american jaguars (Panthera onca) are especially drawn to the civetone in Calvin Klein’s “Obsession.” Good to know if you’re in search of big cats, but it still leaves the question of what civetone actually is and why it is important. For that, I turn to Richard Despard Estes Behavior Guide to African Mammals, in which he describes the olfactory communication of the animals;

Olfactory Communication: scent-marking with dung, urine, perineal gland.

Perineal-gland marks appear to be concentrated on trees fronting roads and pathways, especially trees that produce fruit eaten by civets. A passing civet pauses every 85m or so to press the everted gland against a trunk. The secretion is a thick, yellowish grease that hardens and turns dark brown and more visible with age, while the powerful and disagreeable scent remains detectable for at least 4 months. The musk scraped periodically from the perineal gland of captive African civets is refined into civetone, which “exalts” the fragrances of expensive perfumes.

Why not just cut out the middle-man and press a civet’s butt to your arms, neck, or chest? Such is what a cartoon (and rather low-quality article) from the Softpedia article “Get the best perfume from the cat’s a**” portrays. This is not entirely accurate as the civet’s secretions must be combined with alcohol and other chemicals to bring out its “pleasant musky odor,” but this does not change the fact that for centuries fragrance makers have relied on greasy secretion near a mammals anus to produce more pleasant personal scents.

Fortunately, synthetic civetone has been produced, but many “high-quality” perfume manufacturers still prefer scraping a civet’s musk glad the old fashioned way. From Yilma D. Abebe’s “Sustainable utilization of the African Civet (Civetticus civetta) in Ethiopia” (which is also found complete here);

Despite civet musk being produced artificially in the late 1940’s, high quality perfume producers still prefer the use of civetone (Anonis 1997). Demands for a synthetic alternative have been growing in recent years however with the British Fragrance Association (BFA) and the International Fragrance Association (IFRA) of the opinion that perfume industries are more likely to use artifical musk (Pugh 1998).

Indeed, the harvest of “natural civetone” continues, (despite some web sites suggesting that it has stopped with the invention of synthetic civetone) and while the African Civet is not threatened it does not change the fact that cruel practices have been recorded among civet farmers and wild civets are continually caught to replace those that die of stress in captivity (I’ll leave you to imagine why they’re so stressed).

The author also notes that local superstitions and husbandry practices make the trade very hard to regulate and control, and the process is considered unsustainable (although unlikely to stop because of economic gain associated with civet farms). Also of interest is the assertion that predominantly Muslim farmers in Ethiopia harvest civetone from civets. The author writes;

In Ethiopia, only Muslim communities are practice civiculture. According to oral history the legendary leader Nessiru Allah, who lived in Limu, Keffa, suffered from an eye affliction that was cured by an application of civet musk. Once cured, Nessiru Allah ordered followers of Islam to farm African civets (Mesfin 1995).

So what are we to do? Personally, I would check your own perfumes to see if “civetone” is listed in the ingredients, and even contact various perfume companies to see if they’re using civetone derived directly from civets and to ask for a ban on using the harvested secretions from the carnivores. Even if large companies switched over to artifical civetone, however, the practice would likely survive to some degree in Ethiopia and would be resistant to reform, so local and government workers would have to work with the farmers to ensure humane practices (i.e. scraping civet musk off bars or posts they deposit it on rather than sticking a spoon into the animal’s gland) and open up other economic opportunities so that the farmers are not relying on civets for income (even in the IUCN report mentioned above, civetone seems to be bringing in less and less money to Ethiopia). Such is the problem with humane practices and conservation, however; merely establishing the science aspect will not convince the farmer who needs income from his practices, and care for both the animals and people is needed if a positive change is going to be made.

End Note: Civets aren’t the only animals to be farmed for particular scents or secretions; bears and musk deer (also important to the fragrance industry) suffer similar consequences as well, and both will require seperate posts to do their stories justice.

End Note 2: I’ve corrected some of the mistakes I made in the initial post. I started getting a pretty bad migrane in the middle of writing this so I didn’t entirely pay attention to what I was doing. I’ll have some more posts up when I recuperate.